Traditional financial theory asserts that higher risk should be accompanied by higher expected returns, with risk commonly measured by the volatility of an asset’s daily log returns. This principle suggests that investors who endure greater uncertainty should be rewarded with superior performance over the long run. However, empirical evidence challenges this notion.

Over the past decade, renowned professors and practitioners like Andrea Frazzini and Andrew Ang have discovered something puzzling. Their research showed that historically, stocks with the highest volatility (or highest beta) actually underperformed those with the lowest volatility (or lowest beta). This challenges the classic notion of the risk-return trade-off and suggests that the relationship between volatility and return might be more complex than we thought.

But is there a point where increasing volatility starts to hurt expected returns?

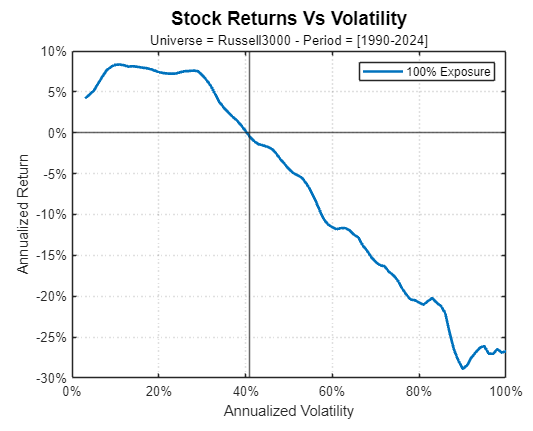

We decided to investigate this using data from 1990 to 2024 for stocks included in the Russell 3000 Index. What we found was both insightful and consistent over time.

Our analysis revealed that the historical annualized return of stocks peaks when their volatility is between 10% and 30%. Beyond this point, returns begin to decline. In fact, when volatility exceeds 43%, stocks tend to become a drag on portfolio performance. This pattern is illustrated by the blue line in the following chart.

This finding aligns with insights from Perry J. Kaufman, a respected quantitative analyst. In an interview with Simon M, Perry mentioned that for his long-only trend model on stocks, he typically starts unwinding positions when volatility exceeds 50%. It appears that excessively volatile stocks may not offer the higher returns that traditional theories would have predicted.

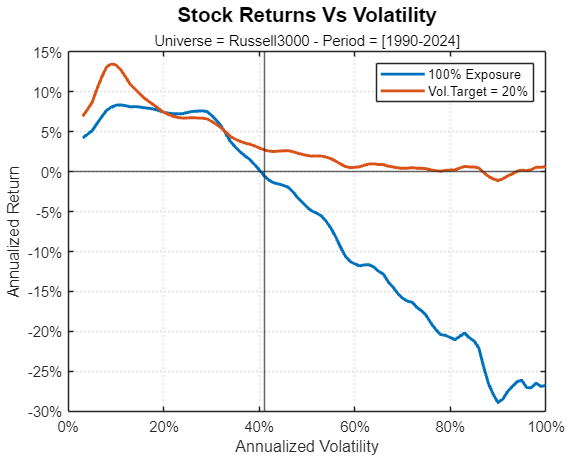

But here’s the good news: a high-volatility stock with a negative expected return can be transformed into a positive contributor to a portfolio.

How?

By simply adjusting its allocation. Using a volatility-targeting approach, essentially dynamically reducing the position size of more volatile stocks, you can achieve slightly positive returns even for stocks with volatility above 40%. This is shown by the red line in the next chart.

These implications might seem counterintuitive, but it underscores the importance of risk management in investing. By carefully calibrating your exposure to high-volatility stocks, you can enhance your portfolio’s performance while mitigating potential downsides.

We’ll be exploring these concepts in more detail in our upcoming paper, “Does Trend Following Still Work on Stocks”, an updated version of the influential 2005 paper by Cole Wilcox and Eric Ryan Crittenden.

Stay tuned for more insights, and feel free to share your thoughts or questions below.

For any further details about this article, feel free to contact me at carlo@concretumgroup.com.